#ExxonKnew

What's Going On?

Atmospheric CO2 measurements at the Mauna Loa observatory (where CO2 concentration has been measured since the 1950s) topped 415 ppm last week, and levels continue to rise steadily. The last time Earth's atmosphere had this much carbon, mastodons, sabre-toothed cats, and giant ground sloths roamed across an iceless Antarctic where beech trees grew. That was 3-5 million years ago, during the Pliocene, and humans did not yet exist.

Keeling Curve | Source: Scripps Institute of Oceanography

Keeling Curve | Source: Scripps Institute of Oceanography

Well That's News...

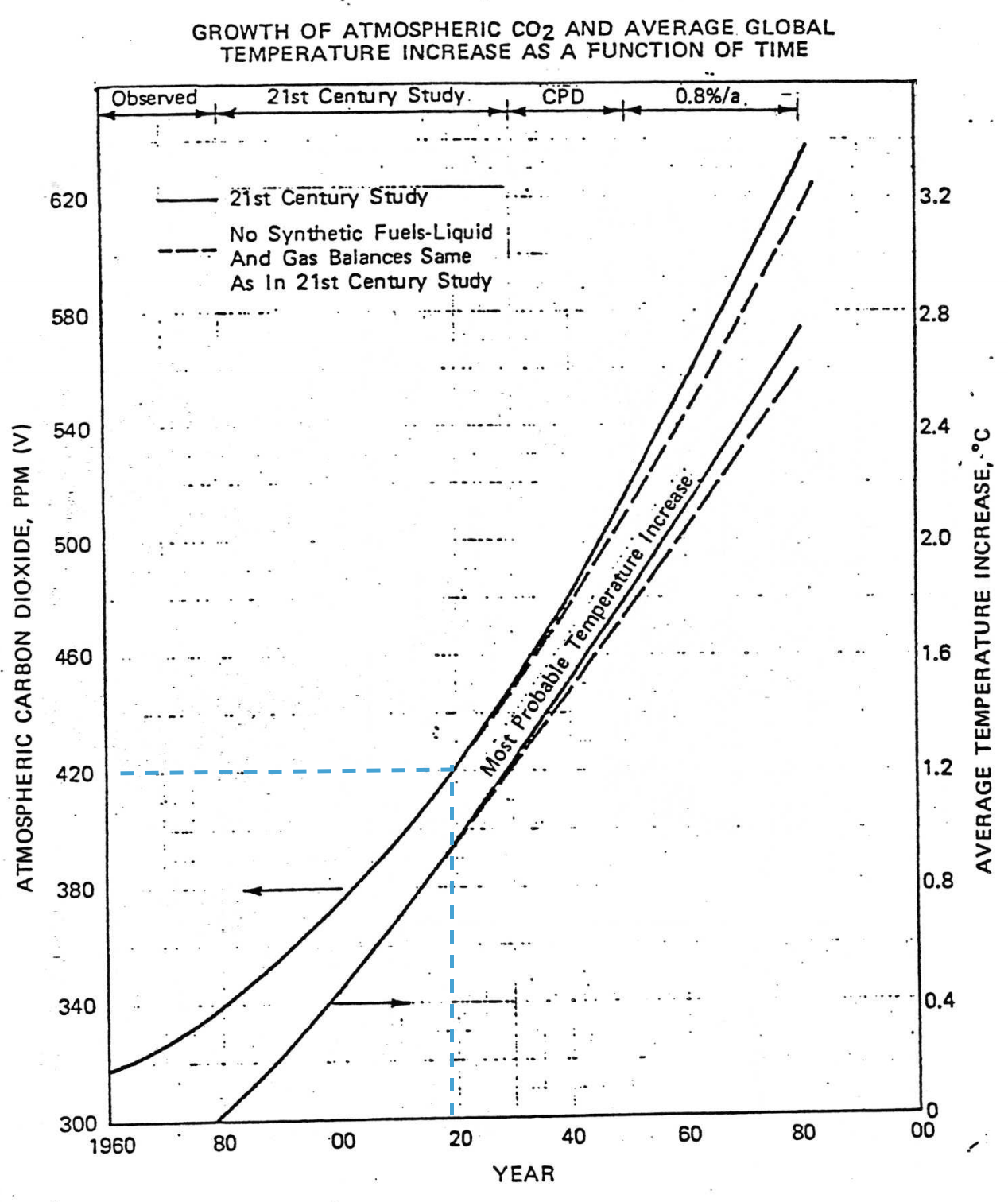

Not to Exxon. They called this one 40 years ago. Recent investigations by InsideClimate and The Union of Concerned Scientists unearthed internal company documents from 1982, revealing that Exxon's research team was performing groundbreaking climate research and very clearly understood the consequences of carbon emissions from fossil fuels on the planet. The accuracy of their predictions are chilling — they anticipated (in their "21st Century Study-High Growth Scenario") that in 2020 atmospheric CO2 levels would fall between 400 and 420 ppm. They also foresaw the accompanying sea level rise, melting of polar ice sheets, change of rainfall patterns, and agricultural failures.

Source: InsideClimateNews

Source: InsideClimateNews

Wow — Give Me The Brief History.

Exxon had a rigorous program of CO2 sampling and climate modeling going on in the 70s. In 1978 senior scientist James Black gave a company talk where he described the "general scientific agreement" that human-produced CO2 emissions from fossil fuels were influencing the climate.

He said, "present thinking holds that man has a time window of five to ten years before the need for hard decisions regarding changes in energy strategies might become critical." Reminder — that was 1978.

Exxon doubled down on their research, and in the early 80s published several papers on climate change in scientific journals, gaining a reputation of "genuine expertise" on the subject. But they stayed cagey on the role of oil on global warming with their shareholders (they're now facing several lawsuits as a result).

The turning point came in 1988, when NASA climate scientist James Hansen testified before Congress, stating that global warming was well underway and steps must be taken to stop it. Sensing an existential threat to their industry, Exxon began a systematic campaign to sow doubt and confusion about the science behind climate change, spinning a narrative that emphasized its uncertain points. They formed a multinational corporate alliance called the Global Climate Coalition to impede government efforts to cut fossil fuels, and helped prevent the US from signing the international 1997 Kyoto Protocol that would have set limits on emissions. Exxon continues its lobbying, funding of right-wing think tanks, and rhetoric of misinformation today.

Sounds Like We Have Ourselves A Proper Villain.

No kidding. Unfortunately, Exxon's campaign has largely succeeded. The seeds of doubt they planted from 1988 onward have delayed critical action for decades — half of all the carbon in the atmosphere was released after 1988.

"All it would've taken is for one prominent fossil fuel CEO to know this was about more than just shareholder profits, and a question about our legacy," says climate scientist Michael Mann. "But now because of the cost of inaction—what I call the 'procrastination penalty'—we face a far more uphill battle."

Turning Out The Lights

What's Going On?

In an effort to hedge against peak wildfire conditions, PG&E could shut off power for up to 5.4 million customers in California this summer. While they only plan to use the tactic as a last resort, it could black out entire counties at once.

What's The Backstory?

Experts laid the blame for 2018's Camp Fire (the deadliest in California history) on faulty transmission power lines owned by PG&E (who provides electricity for most of Central and Northern California). Facing $30 billion in damages from 2017 and 2018 fires, the utility company filed for bankruptcy in January, and just released their state mandated 2019 wildfire plan. They're scrambling to improve their power lines, clear vegetation, and install sensors and cameras to monitor risk areas, but this work could take upwards of five years.

Have Blackouts Happened Before?

San Diego Gas & Electric first thought about trying the blackout strategy after major wildfires in 2007, but held off until 2013 due to complaints. At this point California's largest blackout occurred in November 2018, when 20,800 throughout San Diego County lost power. PG&E performed a trial run in Calistoga last October as strong winds whipped through the city — some spent almost three days without power.

How Do People Feel About It?

Generally pissed off. Former Calistoga city manager Dylan Feik claims PG&E is "essentially shifting all of the burden, all of the losses onto everyone else." The Calistoga experiment left the city rushing to provide medical care for vulnerable residents, spoiled food in grocery stores, closed schools, and forced a ton of hotel and restaurant reservation cancellations in a town largely reliant on wine tourism. PG&E doesn't plan to cover losses due to intentional blackouts, which Feik says "makes good business sense, but from a public policy perspective, it's awful."

At Least The Drought Is Over, Right?

Yep — California is drought-free for the first time in over seven years. But that doesn't necessarily translate to fewer wildfires during the summer ahead. In fact, it makes the state ripe for burning as all the new vegetation that sprouted up over the past few months dries out, providing an endless amount of new fuel. So regardless of the problems caused by blackouts, they may be the only solution for now.

Governor Gavin Newsom has budgeted $75 million to help cities deal with the power shut offs, saying, "I'm worried. We’re all worried about it for the elderly. We’re worried about it because we could see people’s power shut off not for a day or two but potentially a week."

Bison Time

The Bison Decline

Until the late 1800s, tens of millions of American bison roamed on grassland from Minnesota down to Texas. In the 19th century, the US government and Americans killed the animals in massive numbers for sport and as part of an effort to eradicate the main food source of Native Americans. By the end of the century, only 1000 remained — mostly in Yellowstone National Park, Canada, and a few zoos and private ranches.

Source: Cameron Kirby

Source: Cameron Kirby

The Bison Comeback

Just a few decades later, activists like Buffalo Bill and Teddy Roosevelt realized the importance of bison to prairie ecosystems and started campaigns to re-establish the species in the wild. Bison were bred in captivity and reintroduced to their native habitat — by the 1920s their population on the Great Plains surpassed 12,000, ensuring they survive the near brush with extinction.

Where are We Now?

In the 1960's, conservationists, Native Americans, and ranchers (who saw bison as an alternative to cattle) started to bring bison back in much larger numbers. Today, the population runs about 500,000 strong across ranches as well as public and Native American lands. While 90% of the total is raised as livestock (mostly on grassland in natural conditions), the nonprofit American Prairie Reserve, wants to create a 3 million acre preserve for over 10,000 bison in Northeast Montana — which would be the largest bison population in the world.

Why Are Bison So Important?

They're crucial in restoring grassland ecosystems. They selectively graze on grass and are considered a keystone species — plants that would otherwise be pushed out by grasses are able to coexist in areas where bison selectively graze. Since they like to ramble across long distances, they impact the entire prairie and spread nutrients through their waste as they travel. The mosaic grazing patterns and trails they forge create better habitats for plant and animal species in the open prairies — studies have shown that introducing bison back to the land has increased the diversity and abundance of many plant, insect, and bird species.

Weekly Scraps

7 tips for green spring cleaning without toxic chemicals.

Scientists find genetic reason why store-bought tomatoes taste so bland.

Shelves of shame: are these the worst recycling offenders in supermarkets?

Los Angeles fire season is beginning again. And it will never end.

America just had its wettest 12-month period on record.

Why some wineries are becoming 'Certified B Corp' — and what that means.

A truly remarkable spider with a spring-loaded trap.

Scientists discover Hawaiian "supercorals" thriving in warm, acidic water.

Metal straws, mason jars, bamboo forks: do you have to buy more stuff to go zero waste?

Why some wineries are becoming 'Certified B Corp' — and what that means.

UN decides to control global plastic waste dumping.

The dark town that built a giant mirror to deflect the sun.

Trump pushes for new bailouts for farmers hurt by his trade war.

California jury hits Bayer with $2 billion settlement in Roundup cancer trial.

Australia faces 'world-first' climate change human rights case.